“My religion is kindness”

We tend to think of kindness as being nice, but it is so much bigger than that. Kindness is being what it is needed. Sometimes nice is needed and sometimes firmness is needed—and being firm or holding a hard line can actually be the kindest thing. Kindness can just come in all sorts of shapes and sizes—and it’s one of those things—you often know it when you feel it—not because it always feels comfortable, but because it feels like something you can lean on, like you are being held.

Last summer I visited my German Host Parents. I was an exchange student in high school and it was wonderful to go back and visit my German Host Family and experience a range of kindnesses in the present—from being picked up at the airport with warm hellos to wonderful meals, beds made up for you, and train tickets gotten ahead of time, early in the morning. And it was also wonderful to remember the kindness I had experienced as a high school student. I am sure there are things they would remember as kind: the actions they intended as kind—the help with my homework, the vase of sweet peas by my bed, the snacks brought to me as I studied or worked.

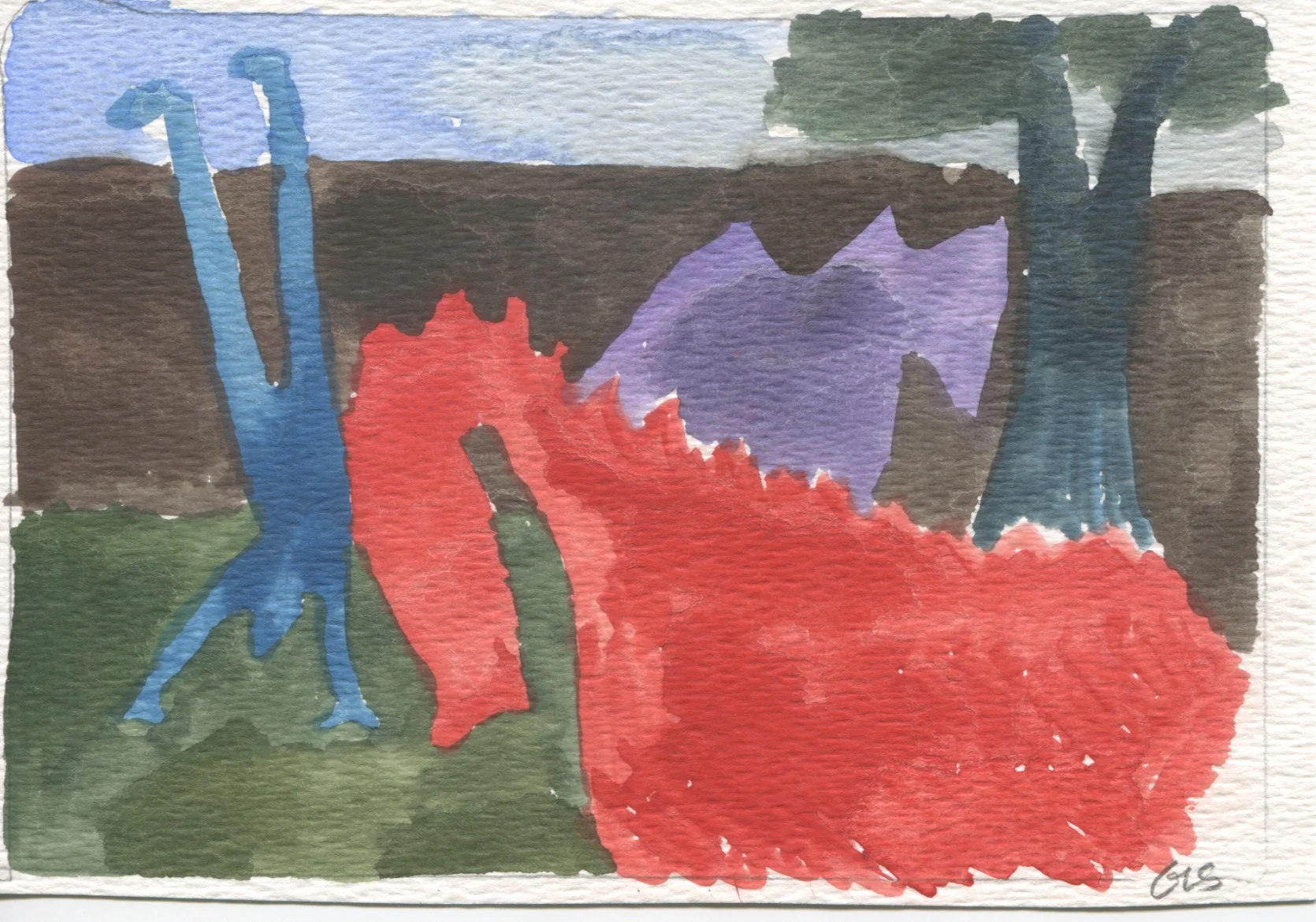

On this trip I was also remembering something I felt as such a strong kindness that they might not remember. In April of that year I had a hard time—and had neither the language nor the skill to talk about it, nor did I really believe in asking for help. I’m pretty sure they knew that I was struggling, but it's also likely that they didn't have the language or the skill to go directly at it either. Instead, I came home from school every day and picked up my paper and watercolors and headed into their garden. They had a beautiful garden and were often in there working, but they left me in peace—neither fussing over my paintings or trying to jolly me out of it. They gave me the space to do what I needed and that was the kindest thing they could do.

We often think of kindness as something that we do for other people or other people do for us, but it is also essential to healing and growing to be able to be kind to yourself. And once again, its not so much about being nice—it’s not retail therapy (though I am not opposed to that)—it’s being what you need—it’s giving yourself what you need. Do you need to go to bed early because you are tired? Do you need to order take-out because you just can’t manage cooking dinner AND everything else? Do you need to take time away from your family to re-group and get your brain back—run errands? Play golf? Or do you need to cancel a meeting so that you can spend time with your family?

Kindness creates an environment for mending and growing. The things that were broken can come together and mend. The parts that are tired can let go and relax. The parts that need nourishment can breathe and look for what they need. That April in the garden had a timing of its own. I don’t remember how I started and I don’t remember how I knew I was finished—but I left the time in the garden more whole. Never underestimate the power of a little kindness—intended or unintended.

© Gretchen L. Schmelzer, PhD 2016/2023