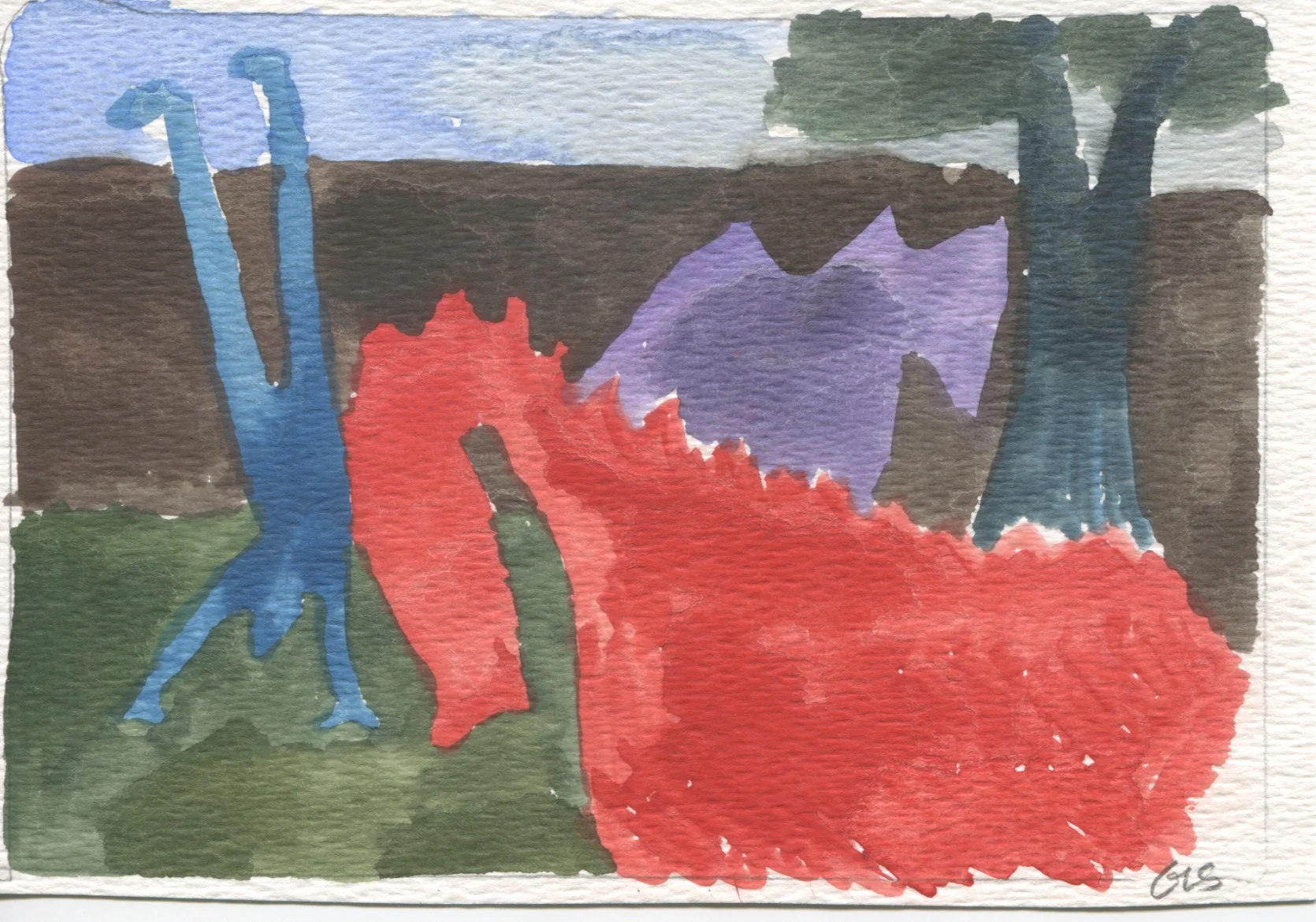

Teaching Dragons to Cartwheel GLS

“What saves a man is to take a step. Then another step. It is always the same step, but you have to take it”

Learning happens when things are just outside of our reach. Out ahead of us where we need to stretch to get to it, but not too far.

Many years ago I read a story called Jeannie about a speech therapist who had been called in to work with a young woman named Jeannie who was mute. She was mute for psychological reasons, rather than physical ones and she was living on a psychiatric ward. She hadn’t spoken for six years and Jeannie’s mother was desperate. She begged the speech therapist to work with her daughter.

Initially the speech therapist said, “No,” because she only knew physiological exercises to improve speech—and physiology wasn’t the issue. But despite there being no need for the speech exercises from a physiological point of view, the speech therapist decided to start there anyway. The exercises were the increments that the therapist knew and by starting with smallest increments—she was able to keep Jeannie’s psychological fears at bay. The speech therapist had the girl make simple phonetic sounds. Sounds coming out of her mouth without the pressure to ‘communicate something in particular.’ This slow pace allowed Jeannie to make sounds, to ‘be in an interaction with someone’ without feeling pressured to communicate and without feeling pressured to ‘be cured’—both of which terrified Jeannie.

The ability to reach to the next step, the step I can take, the step within my reach is not only fundamental to healing—it seems to be built in to how we grow and learn from infancy.

It was a lesson I learned again when my great niece Lyla was 6 months old and was on the verge of crawling. If you put a toy out of her reach, she stretched herself to get it, and even tried to figure out, if it was just a little too far, how to get herself in to position to crawl. She was figuring out how to bring her knees up underneath her, get up on her hands, and start to rock herself into a crawl. But at the time, the skill of crawling still eluded her –when she pushed too hard with her hands and she just slid backwards, away from what she wanted, looking confused at why she wass further away, rather than closer to, her goal.

The most striking thing watching her was what appeared to be an inner sense of what was ‘within reach’—what was a ‘doable challenge.’ If I put her favorite toy too close to her she grabbed it and it was done. She dropped the toy and looked around—bored. If I put the toy too far out of her reach she seemed to somehow know that it was just too big of a challenge—she didn’t even try. She looked annoyed and looked around for something else to pay attention to. But if it was out of her reach, requiring effort, but not in some category that she rated as too difficult, she took on the challenge and tried to get the toy—sticking with the challenge for a long time, even though she often didn’t get there. This magic space, “just out of reach” is clearly where we learn best.

I think so many of the problems of healing and growth come from disrespecting this fine tuned inner sense of what the next step or “just out of reach” is for each of us. I think we are all like Lyla—we know when it’s too easy and we know when it’s too difficult. And knowing this helps us know what the next step could be—what “just out of reach” is for us.

I think we know it the same way Lyla knows it, but our judgments and “shoulds” and inner critics interfere in our ability to hear that inner sense of the next step that is just outside of our reach and respect its wisdom. We judge that step as too small and we put our version of the toy too far out of our reach, and we freeze or give up on the changes we need to make and the healing we need to do.

Lyla doesn’t have anything interfering with this inner sense. She was able to train me to support her staying right in her learning and growth zone. When I placed the toy too far out she looked at me and scowled. And when I moved it in, she went after it. She didn’t yet have some inner narrative of ‘should.’ She’s didn’t have some inner narrative about “I should really be able to already crawl to that toy and I should be able to do it from much farther away, I mean all the other babies can.”

But most of us –rather than listen to the inner sense of what the next step ‘just out of our reach’ is-- believes that we should already be able to do it, already make that step . Whatever that step is—whether or not we are capable of doing it.

When I began trying to talk about my own trauma I found, actually, that I really couldn’t talk at all. I had no language for my own emotions or feelings. And I really couldn’t tell a coherent story –with a beginning, middle and an end-- about anything. I found that when I tried to talk I either became overwhelmed and disorganized—or I shut down and became numb. Trying to tell my story was too hard. It was out of my reach. And instead of being able to ‘just do it’ – I was stuck.

But I was lucky because at that time I was training to become a child psychologist and because of my work with children I understood through years of practice the crucial need for small steps. With every child I worked with I tried to figure out where they were, where they needed to get to, and what was the smallest challenge I could create that would have them stretch towards it with confidence and curiosity, rather than fear or mutiny.

The treatment for phobias is built on this principle of progression. If you are terrified of dogs, you don’t start by buying a dog. You start with the ability to say the word ‘dog’, or a look at a photo of a dog, or pat a stuffed animal or toy dog. You start with the smallest contact with ‘dog’ that you can—without feeling overwhelmed. And this was true for all of my clients—the smallest steps made for some of the biggest changes.

All learning is this way—and healing is really learning—only some of the most difficult learning—because it is both an unlearning and learning. You have to unlearn all of the protections and defenses you used to survive that no longer serve you, and you have to learn new thoughts, behaviors and attitudes that can help you grow again.

In order for me to learn to talk about my emotions and tell a coherent story I started where I often have children start—with drawing a picture and telling a story about it. With children –especially if they are self conscious about drawing—I will play the squiggle game with them. I will draw a squiggle on a piece of paper and they will look at the squiggle and see what it looks like to them and make it in to a picture. Maybe it looks like a lion, or a snake or a flower. The squiggle takes the pressure off of ‘what to draw’ and whether it has to be perfect because they are only choosing what they see and in many ways the picture can’t be perfect because I already ruined the pristine white piece of paper with a scribble. Once they finished the drawing I would get them to tell me a story about it: “Tell me the story of the picture. What is the main character thinking and feeling and doing? What’s going to happen to the character?”

So I decided to start there with myself. I would paint a squiggle in watercolor with my eyes closed. And then open my eyes, decide what the squiggle looked like, and then I would paint whatever I saw in the squiggle. And then I would do one more. And then as the watercolors were drying, I would take out a legal pad and write the story of each of the pictures. I did this almost every day for two years. The stories weren’t earth shattering or important in and of themselves. The stories were practice. They were the practice of a narrative. They were the practice of talking about emotion. The watercolors and the stories allowed me to come in to contact with my own thoughts and feelings and put them into language. This practice stretched me, but it didn’t overwhelm me.

So how do we find the next step we need to take—the one that is ‘just out of our reach?’ As a therapist I think it its hard to assign the next step for two reasons. The first reason is that the next step is a felt sense, and I can’t really know what that is for each person because I can’t feel it. And the second is that if I do have a sense of it, the next step is usually quite small and it can feel to clients like I am suggesting something that is childish or might feel insulting. But as a client I know firsthand that finding the next step is what allowed me to keep moving, to learn what I needed to learn, no matter how small, or ridiculous or childish that next step seemed. So I think it is really important to listen to your inner sense of the next step, and if you can, talk about it with your therapist so that you both can understand where you are—and how far out or close in the next step needs to be.

When I first started teaching mindfulness meditation on an adolescent psychiatric unit , I actually started with a stopwatch. We did breathing exercises for increments of 10 seconds, then 20, and then 30. We built patience muscles in the smallest possible amounts.

Kids aren’t as bothered by increments—and the increments can get wrapped or hidden in play—so they can’t see them for what they are. My child clients didn’t know that they were practicing the necessary skills of patience and anger management as we played the game Sorry - a game where disappointment and loss are built right in to every possible move, requiring you to manage your emotions almost every time you or someone else picks a card. Finding the increments for learning is so much harder for adults and teenagers.

Which is why I think that the smartwatches and FitBits have been so successful. For people who may be unfamiliar, digital trackers allow you to track the amount of steps you do in a day. You can get a goal of steps or distance and know when you meet it each day. Digital trackers aren’t great because they creates a goal of 10,000 steps. They’re great because they make that goal achievable in the smallest possible increments. Increments that are available to you all day long. Your goal can’t disappear and your ability to work at it any time doesn’t disappear. You always have a chance to get to your goal, in the smallest possible increment.

If I had a wish for you, or the organizations I work with it would be to have you feel good—indeed proud—of the small incremental change that real shifts require. I wish I could rig every goal for healing and growth with its own version of the Fitbit—so you could experience your steps and feel proud of them. I want to have your wristband buzz with colorful stars every time you say something brave, or act more assertively or engage in an act of self-care. I want you to feel good about your small steps instead of feeling like the step you need to take is too small. Or childish. Or embarrassing. Instead, I want us all to be looking for that magic space, that space of growth--just out of reach—and embracing whatever step that is, because that simple step is our best chance for healing and growth.

© 2023/2016 Gretchen L. Schmelzer, PhD

The story of Jeannie by Miriam Mandel Levi is in the book Same Time Next Week