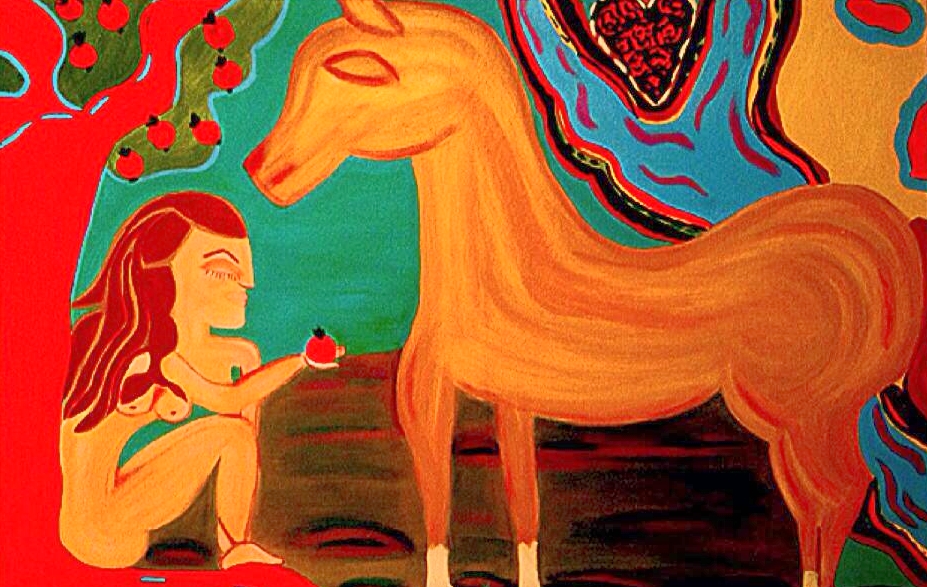

Meet Me Where The River Splits. Artist: Jennifer Wood

When you are in a standoff with yourself—you know you are on the edge of healing. It takes a lot of self control, a lot of discipline and hard work to get through the years during and after trauma. You put one foot in front of the other. You set your mind on getting through each day. And you wear whatever version of armor you needed to in order to survive, and you keep on whatever version of armor that helps you continue to feel safe. And the truth is, on the outside, your armor may be so good, people just see you shining. The years during and after trauma often feel like a giant split: you are living one life on the inside and another on the outside. And the truth is, even if you feel like a mess or even look like a mess, still, no one knows how hard you have been working to hold yourself together –to make it through.

And then when you actually get to the place where you want to heal—want to feel better—and want to take off the armor and just live in peace—you can find yourself at a standstill—in that standoff with yourself. Yes, you want help. Yes, you want to feel better. But now you have to challenge the part of you that worked your guard tower, that stood vigil, that protected you. That part of you that helped you survive. That part of you that you fiercely needed and who you had to completely ignore.

I taught meditation groups to teenage boys in Juvenile Detention as part of my dissertation work. When I did the research on their demographics, I found out that over 70% of the boys had experienced child abuse. Yes, they were in juvenile detention because of something that they had done wrong, but these were teenagers with some serious armor. Because I taught the mindfulness group I got to witness their standoff—their struggle with these two competing aspects (of many) that anyone who heals from trauma has: the longing for safety, comfort, quiet, normalcy and some version of the distrustful, hurt animal, guard dog who stares you down.

In some ways the mindfulness group was the perfect practice field for this standoff—mostly because they were allowed to struggle inside themselves—and not have to do it out loud. They could save face. They could lean in to the longing for calm and safety, and everyone’s eyes were closed and no one would know if they liked it, that they needed it. And they could sit completely still and angry on the days that their inner animal felt threatened. They could stare me down and let me know that there was no way they were letting their guard down that day. But because the activity was about stillness, and nothing else was required of them. They could stay. Their guard dog could stay, and tolerate it the best he could. And that is the edge of healing. That uncomfortable place between the old protections and the new hope. The old protections and the old fears and the possibility of something else. The boys got to live on this paradoxical edge of the early days of healing: lean toward actually safety and feel scared, pull away from safety and feel relieved. And occasionally surprise yourself and lean in and feel better.

You have to be able to live on this edge and go back and forth in it. You have to find a way to be near enough to the wild animal that is yourself and allow it to come to trust you. And if you know wild animals like I know wild animals you know that there are no fast moves. There is consistency, there is trust, there is waiting, there is presence.

And while you are waiting out this wild part of you, it can be helpful to use the time to acknowledge the hard work that your protective self did on your own behalf—and be able to understand its fear in giving up its role as protector.

This is a peacebuilding process more than anything else. A chance for you to honor your protective self for its service and loyalty. A chance to be amazed at its energy, or power, or cleverness. A period of time where you don’t try to change it or hide it or feel shame about it—but instead, you sit with it, nearby, and hold out some peace offering. Let it know that it can no longer run your life, but it can remain in your pasture to heal as long as it needs to.

Let Her Run ~ GLS

“Let her run” I said

to nobody in particular.

She turned around

and looked past me as

she shook her head,

her mane still matted

from a week long stand-off,

no comb, no brush, no hand

upon her at all. But she stood still.

I wanted her to want her freedom.

Wanted her big beast heart

to desire run, desire jump, desire kick.

Wanted her to fiercely fight

for her right as wild animal,

but she stood still. She stared.

My words and wants

meant nothing to her.

Not from the one

who reined her in so tightly

each time she dared to pull,

dared to move

towards what called her.

She did not trust my words,

she feared the bit in her mouth,

yanking her instincts back in line.

She feared my weight

upon her, holding her back.

And now she stood

staring back at me

my mirror-image of disbelief.

Her gaze said I was

asking the impossible

to go, to want, to be

the animal wild that

I had trained out of her.

“She’s still there” I said.

I could see what she couldn’t.

“I am sorry” I said

and she stared back,

dropped her head low

and rolled in the sun.

© Gretchen L. Schmelzer, PhD 2015

The artwork for today's piece was provided by Jennifer Wood. You can see more of her art on her page here

Dissertation referenced above: Schmelzer, Gretchen. (2002). The effectiveness of a meditation group on the self-control of adolescent boys in a secure juvenile detention center. Northeastern University.