In one of my very first blog posts here I talked about an art class I took in college—called Methods and Materials. For my final project I ended up doing giant watercolors of old family pictures—and our class got to have a show of our work in the art building. I had two whole walls.

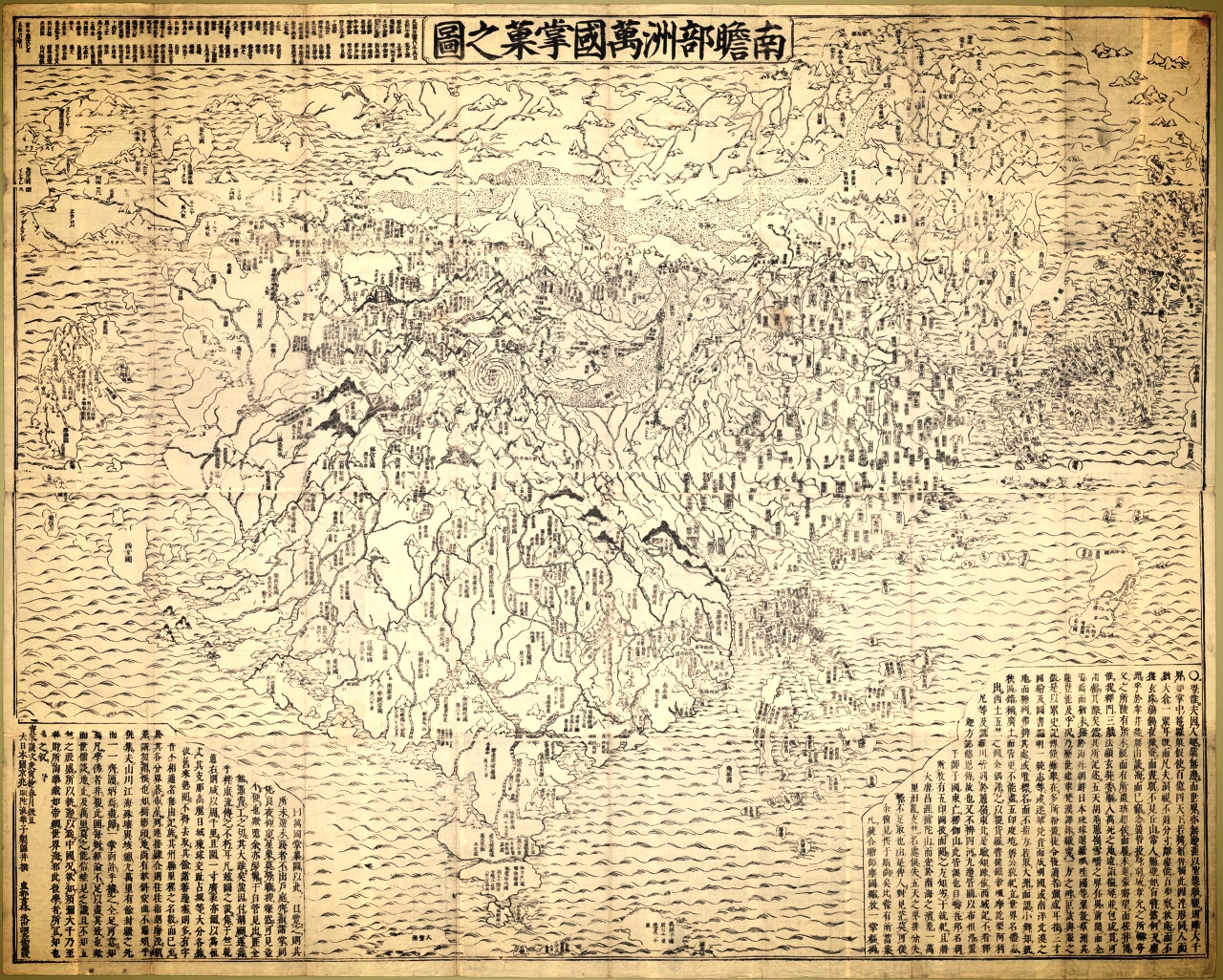

Over the course of the class I became enamored with Chinese hanging scrolls—not so much what was on the inside of the scrolls, but with the outside—the patterns and color block that made the framework for the picture. I thought the frames were as beautiful, sometimes more beautiful than the picture. I made collages of the frames with nothing in the center. And when it came time to hang my show, I created giant hanging scroll frames made of newsprint and maps and sheet music and put my watercolors in the center. I wanted my family pictures to have a framework. Something to hold them tight.

I had no idea then that I would end up traveling to China and Southeast Asia and I now have all kinds of hanging scrolls hanging in my house. Some of them Cambodian, made of fabrics, patterns of silk—hanging from old loom pieces. And some are traditional Chinese scrolls with paintings of bamboo or tigers. They have replaced the paper ones I created in art class.

As a consultant and therapist I often talk about containers or frameworks. These things are the invisible structure that allows change to happen. Not unlike art—we don’t always notice the frame—we take it for granted—the framing of the canvas, and then the frame of the painting—two frames providing structure and support and protection.

And in many ways the container should be invisible and taken for granted. It should be so interconnected that you think it is part of the art.

What do I mean by container or framework? When I teach people about containers and helping I go back to being a lifeguard. When I worked as a lifeguard I had a rule that there should be a lifeguard for every 10 people. At this ratio, it was a safe situation. A lifeguard can watch 10 people and interact with 10 people. Interestingly there is a magic number for human memory which is 7 plus or minus 2. It is what the human mind can easily hold in memory, and I have found that human beings somehow know if there are enough lifeguards or group therapists or consultants of groups to keep them in memory. When we unconsciously know that we are held in memory, we have the experience of knowing there is an emotional lifeguard. And so I have found the lifeguarding ratio to be the best container for work to get done by groups. When you have enough staff, or therapists or consultants—the group does its work and takes risks. When the ratio goes down, the work shifts back to being more superficial.

And the container can also be too tight. If a painting were all frame and crowded out the painting—that wouldn’t be right either. If there are too many helpers, therapists, consultants—people don’t feel safer, they feel scrutinized. In this scenario, they are held too much in memory and they get self-conscious and they don’t do as much work either. So in creating containers there is a balance.

And it is a balance that we participate in whether we are the helper or the one being helped. The helper provides the container in the beginning so healing can happen—it is the cast or splint that you can’t see, but which has to be thoughtfully put into place and adjusted as needed. Tighter when we are in crisis, looser as we heal. As the person helping you have to deeply understand that the container is as much of the work as anything else. And, like the frame of the canvas--it is the prerequisite for any work to happen. As the person getting help you have to learn to lean on it, lean in to it, and let it become something you trust. You come to depend on it, and then you learn to create it for yourself. Healing is so much like the hanging scrolls that I love so much: it requires that you become the beautiful frame and the artwork inside. You are both: the container and the art.

© 2015 Gretchen L Schmelzer, PhD