“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.”

We are Charlie. We are the NAACP. We are Newtown. We are Trayvon. We are Boston. We are Virginia Tech. We remember. We can’t breathe. It feels like we barely get a break from one heartbreak in the world and the next arrives. How do we hold it? How do we hold each other? How do we remember that we are a we?

This past week there was an internet, and mostly Facebook phenomenon of Photo Doggies for Anthony where over 900,000 people (myself included, it was impossible to resist) sent in pictures of their dog to a 16 year old boy who was getting chemotherapy treatment. It just went viral. Everyone so easily, and immediately sent a picture of their dog to this page with the most lovely notes of well wishes. It was a mighty storm of kindness. And I wish we could figure out how to do that more. And by that I don’t necessarily mean doggy Facebook pages, but how can we create mighty waves of kindness? How can we create these storms of love so we could use them for healing and for change? How can we rally around the hurt parts of our world the way we rallied around Anthony? There wasn’t a worry that other people from different political parties or religions or countries were sending in dog pictures. We could be a we. And we need so much more of that.

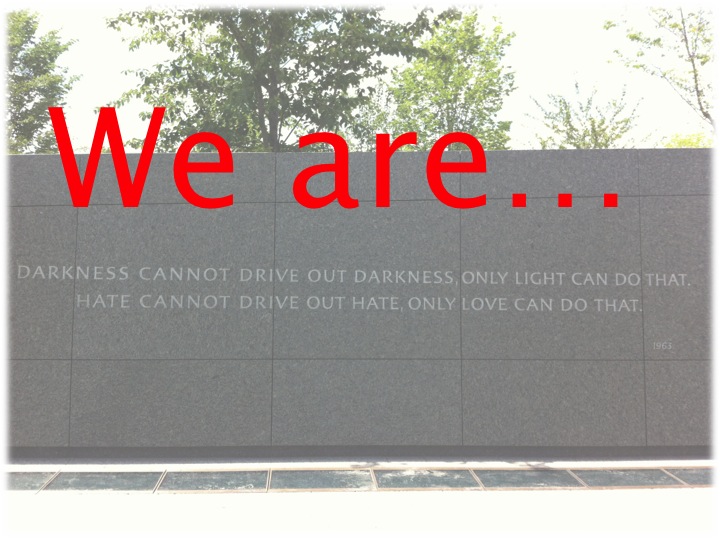

History is full of heartbreak. We are Auchschwitz. We are the Killing Fields. We are the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory. We are Wounded Knee. We are Montgomery. Violence, terrorism, evil—they have a playbook that has been used for a long time. And it is so hard to know how to stop it. It seems that increased attacks, or violence is the only way. Yet, as Martin Luther King, Jr. said,

“Violence never really deals with the basic evil of the situation. Violence may murder the murderer, but it doesn’t murder murder. Violence may murder the liar, but it doesn’t murder lie; it doesn’t establish truth. Violence may even murder the dishonest man, but it doesn’t murder dishonesty. Violence may go to the point of murdering the hater, but it doesn’t murder hate. It may increase hate. It is always a descending spiral leading nowhere. This is the ultimate weakness of violence: It multiplies evil and violence in the universe. It doesn’t solve any problems.”

But what does solve the problems? It feels like the violent and the cruel have a playbook handed down over centuries. Where is the playbook for peace? Where is the playbook for change in the face of heartbreak and evil?

In reading Parting the Waters by Taylor Branch, I felt like I finally came across a playbook for change. The actions of the civil rights leaders in the 50’s and 60’s came as close as we may ever get in some very fundamental structures that they used to create a mighty wave of kindness for each other to hold each other as they sought change. They knew something about the we that we have all forgotten. Martin Luther King’s premise was that we were all a we, even as it was not yet a lived experience, even as there were forces working against that, powerful forces. He started with that premise as an aspiration and he worked toward it. He never let go of the we.

The movement would not have been what it was without the churches and the mass meetings that were held nearly nightly during the most difficult parts of the struggle. That was a structure of we. And the civil rights leaders worked really hard to collaborate and listen and flex with the work as it grew. They struggled and they were imperfect, but they were open to making sure the we could expand.

In a study of why young people join terrorism groups, it wasn’t because they already had strong beliefs about something or their religious fervor. It was actually because they were seeking something to believe in, they were seeking meaning, they were seeking a stronger identity. The same was true when they researched suicide bombers. It wasn’t religious fervor; it was a range of motivations more connected to finding meaning in dire situations. And there has been similar research about why young people join gangs.

Finding meaning isn’t easy. Finding meaning in something means being able to see outside yourself, see the bigger picture, believe in something bigger than yourself. Finding meaning means hard work. But finding meaning rarely happens by yourself. When people are seeking meaning they are also seeking connection and so the question is, ‘how can we all work to create better moments of connection?’ How can we strengthen a ‘we’ that is bigger—how can we see the ‘we’ when tragedy isn’t currently befalling us?

I heard a wonderful story of elders in an Alaskan village who helped combat suicide within their youth. They did it by saying that their youth were their responsibility, that they were a ‘we.’ They decided that no youth should walk to and from school alone. They decided that they would look out of their windows and if they saw a youth alone, they would walk with them to school or walk them home. The suicide rate in the village plummeted. When they were a we, the elders and youth had meaning. And meaning meant life, meaning meant health.

Every act of violence has different roots and different motivations. There is no one answer to these tragedies. But we do know that individual acts of courage, and collective acts of courage have been what has changed the world—whether walking a child home, collectively praying for change, or peacefully protesting injustice. We need to work on our we, because, We are, and we need we.

© Gretchen L. Schmelzer, PhD 2015